For a more in depth lesson go here: Circle of 4ths and 5ths

The 3 Mistakes Guitar Players Make When Trying To Learn Theory, And How To Avoid Them

Note: You can expand this presentation by clicking on the icon in the bottom right of this video player.

[flv:https://guitartheoryrevolution.info/blog/wp-content/uploads/2011/05/gtrp1.flv 500 388]

Lesson 13: Improvising With Relative Major and Minor Scales

Remember you can zoom in and out on the images in this post by pressing Ctrl + and –

Relative scales are scales that share the same set of notes but have different root notes (because they are in different keys). They sound different because their intervals (distance of the scale notes from the root note) are different.

For example here is the C Major scale.

Note Names: C, D, E, F, G, A, B, C

Formula: 0, 2, 4, 5, 7, 9, 11, 12

It sounds the way it does because of the order in which you play the various intervals, from the C to the D (0 – 2), from the D to the E (2 – 4) etc.

But what if you kept the same notes but started on the A in stead? Well then you would be playing the relative (Natural) minor scale of this C Major Scale.

Note Names: A, B, C, D, E, F, G, A

Formula: 0, 2, 3, 5, 7, 8, 10, 12

Using the Five Fret Pattern you can see that although the notes are the same the intervals are different. A to B (0 – 2), B to C (2 – 3) etc.

So to find the relative minor scale of any given Major scale you simply start playing the same notes from the 6th note of the Major scale. To find the relative Major scale for any given Natural minor scale you start at its 3rd note.

In the above diagram you can see all the notes of the C Major / A Natural minor scale.

Can you see where I got the earlier diagram for the C Major scale from? It starts at the eight fret. So if you want an easy way to find the relative minor scale simply start playing from wherever you see an A. Like the example below.

Knowing how to find the relative minor scale for every Major scale is useful for several reasons. First of all it means that if you know how to play the Major scale you automatically know the Natural minor scale as well.If you practice the Major scale in all 12 keys you’ll know its relative minor in all 12 keys as well.

It means that when you are improvising you can easily switch between the two scales to get a different sound.

Listen to this song Otherside by the Red Hot Chili Peppers (the chord progression for most of the song is Am – F – C – G) and play the above C Major scale over it.

Next play the A minor scale. Can you hear how they sound different?

Now use the below diagram to improvise over the music, but rather than sticking to just one scale pattern for each scale, try to play all over the fretboard in stead.

In order to still get the two different sounds choose to switch your focus every 60 seconds or so between the A and C note. So start and end your licks on A for 60 seconds, then start and end your licks on C for the next minute.

For extra bonus points focus on the intervals that are different for each scale: 0-3, 0-8 and 0-10 for the minor scale and 0-4, 0-9 and 0-11 for the Major scale.

Lesson 12: 6th and 7th Chords

Remember you can zoom in and out on the images in this post by pressing Ctrl + and –

In a previous lesson about chord progressions you may have noticed chords with a 7 behind them V7 or IIm7, examples of which are the G7 and Bm7 chords. These are called 7th chords.

7th chords are chords that consist of 4 notes, starting with a Major or minor triad and playing an extra note on top.

Before I show you how to construct and play these chords let me briefly touch on the naming of intervals and chords. The names 7th and 6th refer to intervals used in these chords. So far in these lessons I’ve avoided using the standard interval names, such as minor 2nd and Perfect 5th because in my opinion they only confuse guitar players who are just starting to learn music theory. The number one priority at this stage is to know how to construct chords and scales and to be able to see them easily on the fretboard.

In future lessons I’ll talk more about standard naming conventions for intervals and then you’ll be able to discuss Augmented 9ths and Perfect 11ths with piano and violin players as much as you want.

Using our method of counting the fret distance from the root note you should easily be able to remember the formulas and apply them to the fretboard using the Five Fret Pattern. Remember the formula for the Major triad is 0 – 4 – 7 and for the minor triad it’s 0 – 3 – 7.

Below you’ll find the name of the chord, the common symbol for it, the formula, an image of all the notes for that chord across the fretboard and an example of of a voicing of that chord. Note that the chord shapes shown are moveable along the fretboard, just play the same shape at different places along the fretboard.

Name: Major 7th

Symbol: M7 of Maj7

Formula: 0 – 4 – 7 – 11

Example: BbMaj7: Bb, A, D, F

Example Voicing: BbMaj7

Name: Dominant 7th

Symbol: 7

Formula: 0 – 4 – 7 – 10

Example: Bb7: Bb, G#, D, F

Example Voicing: Bb7

Name: Major 6th

Symbol: 6

Formula: 0 – 4 – 7 – 9

Example: E6: E, G#, C#, B

Example Voicing: E6

Name: minor 7th

Symbol: m7

Formula: 0 – 3 – 7 – 10

Example: Bbm7: Bb, C#, F, G#

Example Voicing: Bbm7

Name: minor 6th

Symbol: m6

Formula: 0 – 3 – 7 – 9

Example: Bm6: B, D, F#, G#

Example Voicing: Bm6

Learn the formulas for each of these chords and see how many different ways you can play them along the neck, there are quite a few positions for each chord.

Lesson 11: Standard Music Notation For The Guitar Player

One of the challenges for guitar players wanting to learn how to use standard music notation is knowing where on fretboad to play what’s written down on paper. It’s one thing to read music notation and another thing to then play it on the guitar.

This is why tablature is so popular with guitar players, because it shows them exactly where on the fretboard they should play. The downside is that tablature doesn’t convey time, tempo and rythm.

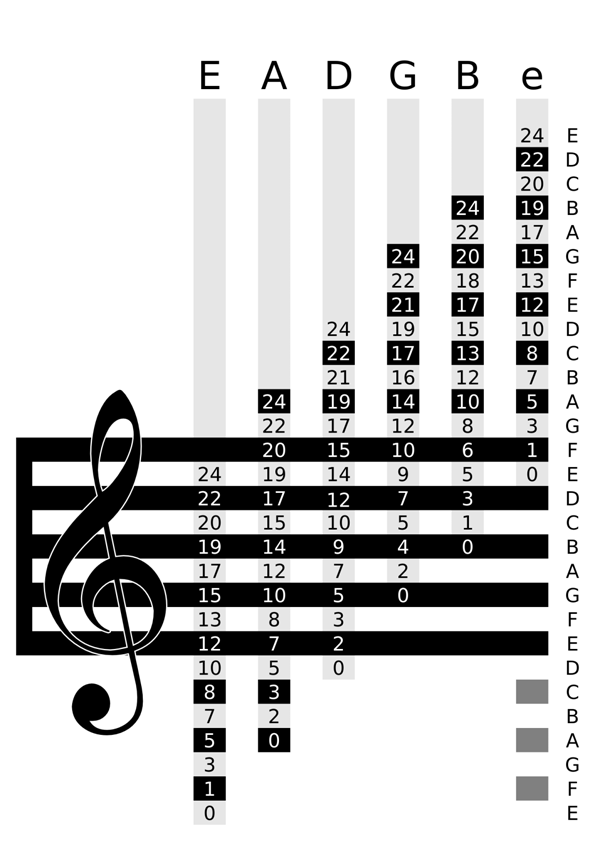

The following diagram is a great tool for bridging the gap between standard music notation and tablature.

Key

- The letters along the top from left to right are the note names of the strings from the thickest to the thinnest string.

- The numbers indicate the fret location, from 0 (not fretted) all the way up to the 24th fret (if your guitar spans two octaves).

- The letters down the right hand side indicate the note name at that particular fret number and string. This example is for the Key of C.

As an example lets see where we can play the notes from the above diagram. E, G, B, D, F. Which we can remember with the mnemonic Every Good Boy Deserves Food.

The E is on the bottom line of the musical staff. If you look on the diagram below you can see there are three numbers on the lowest of the five black lines. The numbers are the 12 on the E string, the 7 on the A string and the 2 on the D string.

This means that the E on the musical staff above can be played at the 12th fret of the low E string, the 7th fret of the A string and the 2nd fret of the D string.

These note locations aren’t something you’ll be able to learn overnight. My advice is to concentrate on learning the note locations for the common chords that you play so that you can recognise them when they’re presented to you in standard music notation. For example learn the music notation for these chords.

After that you should start paying attention to the notation of songs that you’re learning to play, not just the tablature. Many song books feature both tablature and standard notation which you can use as a good opportunity to improve your sight reading.